HISTORIC US WWI UNIFORMS: FROM CAVALRY TO FLYING JACKETS

Introduction

When people think about US WWI uniforms, they usually picture a doughboy in an olive drab wool coat, puttees, and a steel helmet. That picture is correct, but it does not show the full range of what American soldiers and airmen actually wore. Pilots climbed into open cockpits wrapped in heavy leather flying jackets, while older styles from the horse cavalry were still shaping the cut of breeches, boots, and hats.

Here’s the problem: it is easy to mix all of this up.

Many fans confuse a WW1 flying jacket with later bomber jackets. Others see an 1880s cavalry blouse and assume it has nothing to do with the war in 1917–1918. This makes it hard to build an accurate reenactment kit, buy the right reproduction, or understand what men actually felt on their bodies in the field.

If you are a collector, a reenactor, or just a curious reader, that confusion can be frustrating. You might look at museum photos or online sales and see many different colors, cuts, and details. It can feel like there are no rules.

The solution is to look at the story as a line, not as separate boxes.

In this article we will:

- Break down features of the US WW1 flying jacket

- Look at the US cavalry uniform around 1880

- Explain how they fit into the larger picture of US WWI uniforms

- List pros and cons based on real field use

- Share some mini case studies and finish with handy FAQs

Origins of US WWI Uniforms

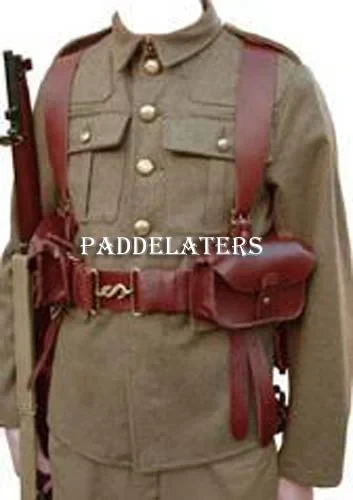

By the time the United States entered WWI in 1917, the army had already moved away from bright dress uniforms. The dark blue coats of the Civil War and Indian Wars had been replaced by olive drab service dress.

Typical items for a WWI enlisted soldier (“doughboy”) were:

- Wool service coat (often the M1917 pattern)

- Matching wool breeches

- Puttees or canvas leggings

- Ankle boots

- Steel helmet or earlier campaign hat

The service coat was made from thick wool in some shade of olive drab, with a stand-up collar and large metal buttons. Under it the soldier wore a wool shirt and sometimes a sweater. The color was chosen because it blended fairly well with mud, grass, and trees, unlike the deep blue of older uniforms.

Even with this new look, older habits and cuts remained:

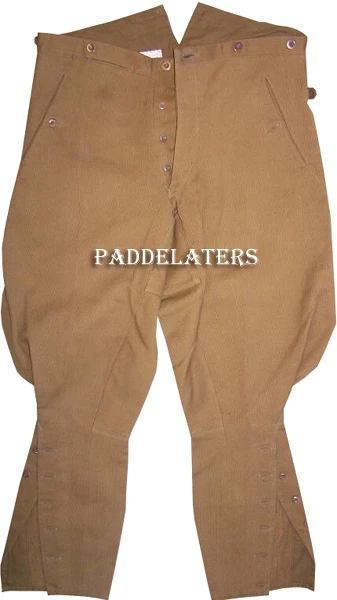

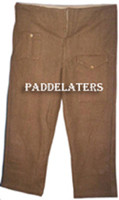

- Breeches kept the wide-thigh, narrow-calf shape that worked well for riding.

- Officers and some enlisted men still used campaign hats that had grown out of late 19th-century patterns.

- Leather equipment and boots were based on long cavalry experience.

And then there were the men who left the ground altogether: the new Army Air Service.

The US WW1 Flying Jacket

When you hear “WW1 flying jacket,” you might think of a neat waist-length jacket like the later A-2. But in the First World War, US pilots usually wore long leather flying coats and layered gear rather than a single standard short jacket.

Most American airmen in France wore:

- The regular wool uniform (breeches, shirt, sweater) as a base layer

- Tall boots or shoes with leather leggings

- A long, heavy leather flying coat or jacket

- Leather flying helmet

- Goggles

- Gloves and often a scarf, usually silk

Key features of the flying coat or jacket

While patterns varied, common details were:

- Material: Thick leather, such as horsehide or cowhide, sometimes with fur trim

- Length: Often mid-thigh or even knee length to keep the torso and upper legs warm

- Closure: Buttoned or belted front, sometimes double-breasted for extra wind block

- Collar: Large collar that could flip up; some had a strap to close around the neck

- Lining: Wool or fur lining in many cold-weather versions

These coats were designed for survival in:

- Open cockpits

- High wind

- Cold air at altitude

- Oil spray from the engine

There was no single strict model. Some jackets were US-made; others were British or French patterns picked up while training overseas. Many pilots bought extra items privately. Because of this, original photos and surviving examples show a mix of styles, from simple single-breasted coats to elaborate fur-collared designs.

Still, the core idea was the same: wrap the pilot in leather and wool to keep him warm and protected long enough to fly the mission.

From 1880 Cavalry to WWI

To see why WWI pilots and doughboys still wore breeches and tall boots, we need to go back a few decades to the US cavalry around 1880.

Features of the US cavalry uniform c.1880

In the early 1880s, the army was fighting and patrolling across the American West. The cavalry uniform of that time had to work on long rides and tough field service.

A typical enlisted cavalryman wore:

- Dark blue wool blouse, often the 1883 pattern with a five-button front

- Dark blue trousers or breeches, with yellow piping on dress items

- High riding boots or shoes with leggings

- A felt campaign hat or slouch hat

- Leather belt, cartridge boxes, and other horse equipment

The 1883 blouse dropped some of the decorative piping and trim of earlier coats to save cost and weight. It was more plain and functional, but still clearly marked as US Army by the cut and buttons. Officers often bought slightly finer coats and might add a vest or private hat, but the basic look was similar.

How this feeds into US WWI uniforms

The link to WWI is not about color, since blue turned to olive drab. It is about shape and habit:

- Breeches and boots: The cavalry had long used riding breeches that were roomy in the thigh and snug at the calf. This pattern carried into the new olive drab service dress. When the Air Service formed, it was natural to pair flying coats with the same riding-style breeches and tall boots.

- Campaign hats: The wide-brimmed felt hats worn by late 19th-century troops evolved into the campaign hats seen on early WWI soldiers, especially before steel helmets became standard.

- Leather skills: Supplying saddles, reins, boots, and holsters meant the army already knew how to produce and maintain leather items. When pilots needed strong leather coats and leggings, the system and mindset were in place.

So when you see a WWI pilot in photos—breeches, boots, leather coat—you are seeing the cavalry tradition adapted for the air.

Pros and Cons in the Field

Now let’s look at these uniforms as tools. What worked? What did not?

US WWI wool service uniform

Pros

- Warm: Thick wool kept body heat even when damp. This mattered in cold trenches and rain.

- Durable: The fabric handled wear from marching, kneeling, and carrying gear.

- Low-visibility color: Olive drab softened the outline of the soldier against mud and grass.

- Simple shape: The straight, no-frills cut made mass production faster and cheaper.

Cons

- Uncomfortable when soaked: Wet wool grew heavier and could feel stiff.

- Itchy for many wearers: Some soldiers found the coarse wool scratchy on the skin.

- Color variation: Different manufacturers produced slightly different shades of olive drab, so jacket and trousers did not always match.

- Hot in warm weather: In training camps or summer conditions, men overheated easily.

WWI flying jacket and pilot’s gear

Pros

- Protection from cold wind: Heavy leather and lining shielded pilots from freezing slipstream at altitude.

- Barrier against oil and dirt: Leather stood up well to engine oil, castor oil from rotary engines, and general grime.

- Layering ability: Leather coats could be worn over wool shirts, sweaters, and even standard service coats, so pilots could add or remove layers.

Cons

- Bulk and weight: Long leather coats could be heavy and restrict movement in tight cockpits.

- Irregular supply: Because there was no one standard pattern, quality and warmth could vary from unit to unit.

- Maintenance needs: Leather needed drying and greasing to stay flexible; in wartime conditions this was not always done.

US cavalry uniform c.1880

Pros

- Good for riding: Breeches, boots, and short wool blouses worked well in the saddle. They allowed freedom of movement and reduced chafing.

- Hard-wearing: Wool and leather stood up to long patrols and rough conditions on western posts.

- Simple enough to adapt: The basic five-button blouse could be used with or without linings for different climates.

Cons

- Poor camouflage: Dark blue stood out against dry grass, sand, and rock. This was one reason khaki and olive drab replaced it later.

- Hot in warm climates: Blue wool could be very uncomfortable in summer heat.

- Mix of private and issue items: Officers’ private coats and hats sometimes broke the visual unity of the unit.

Real-World Examples and Mini Case Studies

Here are a few concrete examples that bring the uniforms to life.

- Preserved WWI pilot’s outfit in a museum:

Many air museums display a full WWI pilot’s rig: wool breeches, tall lace-up boots, leather leggings, thick double-breasted leather coat, helmet, goggles, and scarf. Standing in front of one, you can see how bulky the outfit is and how serious the need for warmth was. - Surviving doughboy uniforms in collections:

Original M1917 service coats often have small moth holes, worn elbows, and faded sleeve chevrons, but the overall shape is still strong. Collectors note that lining color, collar style, and tiny stitching details vary from maker to maker, which matches the wartime rush to produce millions of uniforms. - 1880s cavalry blouse in a regional museum:

An 1880s cavalry blouse on a mannequin usually appears shorter than later WWI coats and has a simpler front—five buttons, no pleated pockets, and plain cuffs. Yellow chevrons on the sleeves and a cavalry saber or carbine on the mannequin help viewers connect the uniform to the mounted branch. - Modern reenactment group:

Some living-history groups portray US WWI pilots or cavalrymen. Watching them dress and move, you see how breeches and boots help on horseback or in a cockpit, and how heavy wool and leather feel during a long day. These groups also show the practical problems: heat in summer events, care of leather gear, and the challenge of matching original shades of fabric.

FAQs

1. What did a standard US WWI soldier wear in combat?

He wore an olive drab wool service coat, wool breeches, puttees or leggings, ankle boots, and a steel helmet. Underneath he had a flannel shirt and sometimes a sweater. Webbing carried ammunition, a canteen, and other gear.

2. Were WW1 flying jackets short like later bomber jackets?

Most were not. Early US pilots usually wore long leather flying coats or heavy jackets that reached at least mid-thigh. The neat waist-length styles like the A-2 came later, between the wars.

3. What color were US cavalry uniforms in the 1880s?

They were mainly dark blue wool, with yellow piping or stripes used to mark the cavalry branch on dress trousers and chevrons. Hats were felt in natural shades, and leather gear was usually brown or black.

4. Why did the army move from blue to olive drab?

Blue was easy to see at a distance, especially in dry or open country. As firearms became more accurate and warfare more focused on concealment, the army shifted to earth tones such as khaki and olive drab that blended better with the ground and vegetation.

5. Can I mix WW1 and 1880s pieces in a reenactment kit?

It depends on the impression. A pure Western cavalry portrayal should stick to 1880s patterns, while a WWI doughboy kit should use olive drab service dress. However, early airmen using breeches and boots show how some cavalry habits carried over, so a flying impression can legitimately mix riding-style lower garments with later leather flying gear.

6. How can I start collecting US WWI or cavalry uniforms?

A good first step is to visit museums, study original garments up close, and read simple guides on patterns and dates. Start with smaller items, such as caps, belts, or insignia, and only move to full uniforms once you feel comfortable spotting reproductions and alterations.

Conclusion

US WWI uniforms were part of a long chain of change rather than a sudden break from the past. The olive drab wool coats and breeches of the doughboy came from years of trial and error in the field. The heavy leather flying jackets of World War I pilots were quick responses to new needs in the air but still rested on familiar riding clothes and leather skills. The blue wool and riding gear of the US cavalry around 1880 played a real role in shaping how American soldiers and airmen looked a generation later.

REQUISITION RELATED GEAR

EXPLORE MORE FIELD REPORTS

Browse all published guides and history articles.